March 2008

Volume 11, Number 4

| Contents | | | TESL-EJ Top |

|

March 2008

|

||

|

britishcouncil.es>

britishcouncil.es> britishcouncil.es>

britishcouncil.es>

Play is older than culture, for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing. We can safely assert, even, that human civilization has added no essential feature to the general idea of play. (Huizinga, 1950, p. 1)

When people learn to play video games, they are learning a new literacy (Gee, 2005, p. 13).

The term serious game is often used to refer to "games used for training, advertising, simulation, or education"(serious game, Wikipedia, 2008). In this article, we use the term computer game in its broadest sense, believing it to encompass the broad spectrum of what is usually referred to now as all digital gaming (video games, console games, online games, etc.). Our presentation for the Webheads in Action Online Convergence in May 2007 (WiAOC2007), on using computer games with language learners gave us the opportunity to explore the following broad areas:

The original slide show from our presentation at the WiAOC2007 is presented below, and you can also access a recording of the presentation at Learning Times [http://home.learningtimes.net/learningtimes?go=1563011]. However, the opportunity to revisit the presentation for TESL-EJ has also allowed us to reappraise and update the areas we covered. In this article we have also decided to concentrate on the free online games, which are perhaps of more practical value to the practitioner.

|

http://www.slideshare.net/bcgstanley/wiaoc2007-games-may-2007 |

To our way of thinking, play is the direct opposite of seriousness...Examined more closely, however, the contrast between play and seriousness proves to be neither conclusive nor fixed...for some play can be very serious indeed. (Huizinga, 1950:5)

As Steven Johnson (2006) points out in his controversial study, "Everything Bad is Good for You," a new generation of students are growing up on computer games, and this is changing their expectations of and demands on education. We need to be able to engage these learners by appealing to their interests and make our language teaching relevant to their world. Occasionally using computer games as an aid to language teaching is one way of doing this.

Thanks to Johnson (2006), Prensky (2001, 2004, 2006), Gee (2005, 2007) and and other serious games researchers, the educational value and learning potential of computer games is finally being taken seriously and long-held myths are being debunked (Jenkins, 2007). Computer games, however, have yet to make a serious impact in the sphere of language learning. Gee (2005, 2007), is one who has covered some ground, and isolated studies exist (Lingual Gamers, 2007), but ideas and help for teachers interested in using games in the language class are still difficult to find.

I'd rather play normal games than educational games but if I had to choose from teachers or educational games I'd choose educational games. (Zarqa, 13, BBC, 2004)

Most gamers nowadays play games on home consoles such as the Playstation2 or Xbox360, Nintendo Wii, or by using portable games systems such as the PlayStationPortable or NintendoDS. There is nothing to stop teachers from getting learners to bring portable games consoles to class, but teachers can also engage learners more simply by referring to them. In this way, the real world of the learner who is a gamer is being acknowledged in the classroom.

Teachers worry about the increasing competition of exciting games and other media for their students' attention, and about students' declining interest in schoolwork. And the kids themselves, of course, are frustrated by the wide gap between their exhilarating experiences playing games and their slow-paced lessons in school. (Prensky, 2006, p. xvi)

Although using console games in the language classroom may prove to be difficult (access to equipment, expensive games, etc), there is nothing to stop the teacher from using examples from popular games made for the Playstation2 or Xbox360 or Nintendo Wii or any of the other games consoles, in class. Teachers frequently ask the question "What TV programmes do you like?" or "What film have you recently seen?" but our guess is that few teachers ask learners about the games they play, or use the characters or stories from games as examples in class. Given the evidence presented by people such as Prensky (2001, 2004, 2006), perhaps they should: Trends show that people are spending more time playing computer games in their leisure time, at the expense of television viewing and cinema attendance.

Why not ask learners to compare different game characters (images are readily available on the Internet)? Or to write a story based in a game world (one that they know well)—having spent more time there than watching a two-hour film, they can probably describe this better. There are many more activities that can be done, but they lie outside the scope of this article.

I wouldn't buy a game just for the educational benefit, it has to be enjoyable too. Some educational games are fun, but usually the fun ones are very well disguised as educational games so they sell more. (Kayla, 14, BBC, 2004)

For language teachers, perhaps the most useful way of engaging learners is by exploiting free online games. Readily available on the Web, we will show how they can be quickly and easily adapted for use in a computer lab. There are also many commercially available language learning CD-ROMs and websites specifically designed for language learning that incorporate computer games. These lie outside the scope of this article. However, anecdotal evidence (quotes such as that mentioned above) suggests that many of these educational games are more "educational" than "fun." An alternative to using this type of game is to instead choose existing games that have been proven to be fun and to build tasks around them to exploit language. This is what is covered in this section of the article. Many of the games mentioned here, with their emphasis on fun, are more engaging to students, and many have authentic language in context that is often hard to find in the games that have been produced specifically for learning.

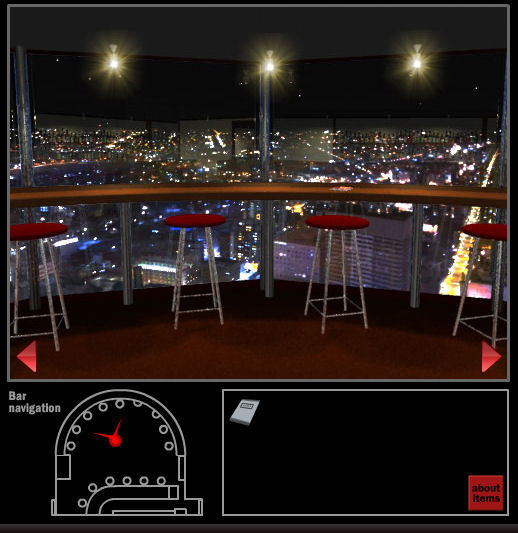

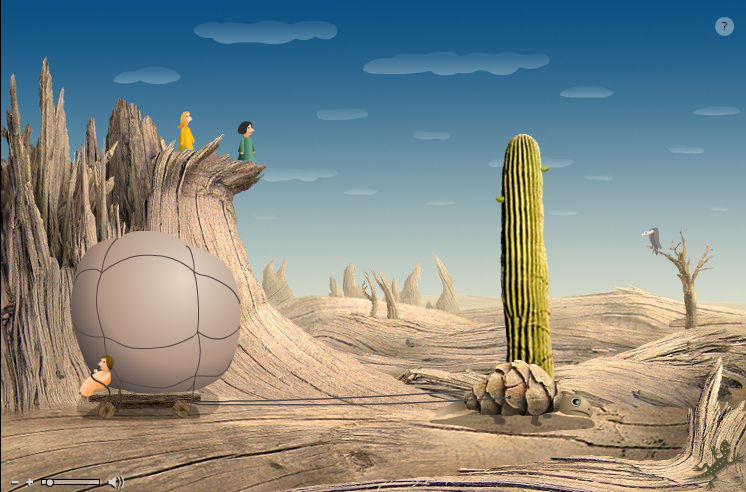

There are many different types of online computer games, but not all are appropriate for language learning. One type of popular online game which is suitable is the logic game whereby you have to solve puzzles, or find hidden objects which in turn allows you to escape to the next level. The games of this genre that we recommend include MOTAS (Mystery Of Time And Space, [http://www.gotmail.jp/bar/]), Escape from the Bar, [http://www.gotmail.jp/apps/bar_e.html] and Samorost2, [http://www.samorost.net/samorost2/] . There are many more (see Mawer, 2008). A variety of activities can be prepared to convert these types of games into language learning tools.

One way to transform games into learning tools is to create an information gap exercise of the game. First, find a text to base your activities on by searching for the name of the game plus the word walkthrough. A walkthrough provides a teacher with a textualised explanation in English on how to complete the game. This text can then be adapted in several ways, for example:

Take the walkthrough and remove target language that the student has to complete while progressing through the game. For lower levels it is better for the teacher to select language items to be removed that are familiar, and provide a list. For higher levels the student may be able to guess meaning from the context of the game. Example: (using a MOTAS walkthrough):

Look under the pillow to find the _________ and take the _________ from the wall. Use the _________ to open the _________ . You will find a _________ in the _________ .

Missing words: locker, screwdriver, key, box, poster,

This follows the relay dictation method, but adapted to a game. A walkthrough text, either printed or on a screen, is placed at a distance from paired students at a computer. Students take it in turns to relay the information in the walkthrough to their partner at the computer. Each pair is encouraged to exchange the information using their own words rather than the literal walkthrough. This activity is very good for descriptive language.

This can be done with any one of the games by adapting the walkthrough text. Each group has different information from a different part of the text and they must ask the other student questions about the part of the text they need. In this way students work collectively to gain understanding and complete the task.

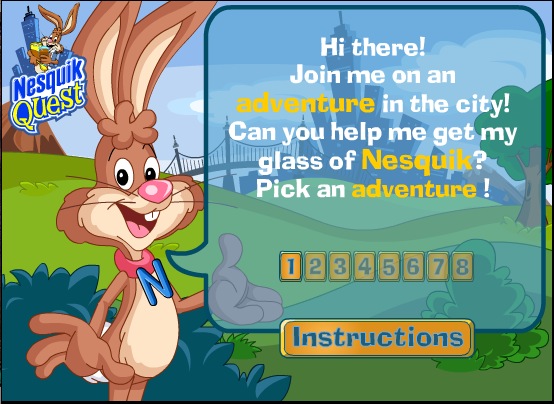

The dictogloss method of dictation can easily be adapted to games. Students watch the teacher play the game and write the main words and short phrases that a particular task within the game needs. Each group is given a section of the game and is encouraged to watch and exchange information. This usually works better if the action within the game flows quickly. Working with someone from a different group, they then write the walkthrough or cheat for the game. As they will not have managed to write down the whole game from the watching exercise they will have to use their imagination and fill in the gaps. This gives them an excellent opportunity to work on grammar. This example lesson below is based on the Nesquik game and is good for intermediate levels and above. The pre-gaming and while-gaming tasks give plenty of practice with park, street, shopping centre and zoo vocabulary. As the teacher is the only person playing the game, this activity is ideal for teaching situations where there is only one computer in a classroom.

Example question card: (from the Samarost2 game walkthrough):

Student 1: Put ______. Pick up the sausage and hang ______. When the green monster hand moves away, ______ .

Student 2: Put all the fruit from the basket on the right into the basket on the left. Pick and hang at the skull. When the green monster hand moves away, press the red button.

Instructions: Ask your partner questions to find out what to do next.

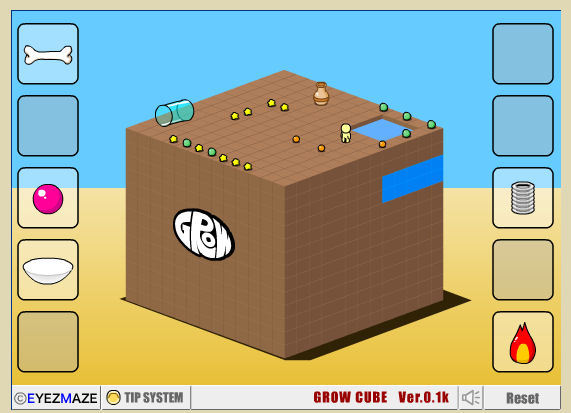

You can make greater use of the walkthroughs of some games with a strong narrative (such as Grow Cube), giving students the text without additional tasks. Here, students' need to comprehend the text in order to complete the game. In this sense the game becomes the comprehension check of the text.

In this activity, the aim is for students to produce their own walkthrough, or narrative text. While playing the game, students take notes on how to complete the game. Before this, it is a good idea to have a pre-playing or during-play task that helps students with vocabulary in the game they may not know. After they have finished the game, the post-playing task asks them to write the walkthrough or to write what they did as a narrative, giving students plenty of practice on past tenses. This is especially good for intermediate levels and above.

This is a good task for lower levels because students only have to focus on a minimum of vocabulary. Students look at the beginning of the game which has lots of things that they can see and therefore write in their vocabulary books. You can teach and/or test vocabulary by asking a series of true/false questions and asking them to put a series of events in order. Here is an example of this task using the game The Bar:

In this instance the teacher holds the walkthrough text and proceeds to go round the class answering students' questions on how to proceed. It is best to do this in combination with a Gap-Fill or Observe/Vocabulary task. The language input is controlled by the teacher so student confidence in spoken English can be encouraged, and the language can be sufficiently rich and at an appropriate level. This type of activity is perfect for working on description and question forms.

A relatively recent phenomenon has been the rise of the MMORPG. These games, the most popular of which is called World of Warcraft, involve players in a richly complicated 3D world populated by thousands of other players and non-player characters. Players choose a character to role-play and advance in level by completing quests set by the game. Usually, after some time playing alone, a player has no choice but to join with other players in order to complete the more difficult quests. This has led to considerable social interaction between players, either using text chat and/or voice. Some teachers have started to explore the fact that much of this communication in these virtual worlds takes place in English to see if they can be exploited for English language learning (Gamasutra, 2007).

Even the interaction between non-player characters and the players in these games can be sophisticated. What is clear is that much has changed since the rudimentary set of verbs and simple speech exchanges which Poole (2000, p. 119) indicates was the cause of much frustration to adventure game players in the 1980s: "Players of the ZX Spectrum version of The Hobbit might remember frustratedly trying to use a wizard's muscle with the command TELL GANDALF BREAK DOOR." Now, the language exchanges that occur between NPCs (non-player characters) and the vocabulary that they understand and use is much richer, and provides much more opportunity for language learning and practice.

I worry about the experiential gap between people who have immersed themselves in games, and people who have only heard secondhand reports, because the gap makes it difficult to discuss the meaning of games in a coherent way (Johnson, 2006).

Many 3D virtual worlds are similar to games in look, but they do not have a plot. This makes them even more attractive to educators, who can use them as a platform to build an engaging learning experience that does not necessarily involve killing dragons. There are now hundreds of virtual worlds to choose from, but at the moment, most educational activity seems to be taking place in the virtual world of Second Life [http://www.secondlife.com].

Whilst not a game, Second Life also has the ability to captivate and shows great potential for education. There are over 120 universities teaching, researching, or working in Second Life (Sim Teach wiki, [http://www.simteach.com/wiki/]) and many people, such as Stevens (2006) and Vickers (2007) have written about the potential for language learning using this platform. There are now virtual language academies working there (http://www.avatarlanguages.com and http://www.languagelab.com are the two most interesting ones) and the British Council [http://www.britishcouncil.org/learnenglish/] have opened a self-access centre island for teenage language learners in the teen grid [http://www.teen.secondlife.com] of Second Life, a space designed exclusively to be used by teenagers and approved adult educators. You can find out more about this by watching the slideshow below.

|

http://www.slideshare.net/bcgstanley/learn-english-second-life-for-teens |

Good video games reverse a lot of our cherished beliefs. They show that pleasure and emotional involvement are central to thinking and learning. They show that language has its true home in action, the world, and dialogue, not in dictionaries and texts alone (Gee, 2007, p. 2).

Predicting the future is at the best of times, difficult, but the growing interest in the use of games in education in general indicates that this could become a very interesting and active field of exploration in language teaching and learning in the future.

Graham Stanley is the product development manager for the British Council 'Learn English Second Life for Teens' project and works as senior teacher at the British Council Barcelona Young Learner Centre.

Kyle Mawer is project officer of the British Council 'Learn English Second Life for Teens' project and teacher at the British Council Barcelona Young Learner Centre.

BBC. (2004). Would you buy educational video games? Children's BBC Newsround. Retrieved March 1, 2008, from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/cbbcnews/hi/chat/your_comments/newsid_3569000/3569882.stm

Ferlazzo, L. (2008, January 1). Free online games develop ESL students' language skills. Tech Learning. Retrieved March 1, 2008 from: http://www.techlearning.com/story/showArticle.php?articleID=196604915

Gamasutra. (2007). Using World of Warcraft to teach English. Retrieved February 28, 2008 from: http://www.gamasutra.com/php-bin/news_index.php?story=13341

Gee, J.P. (2005). What video games have to tell us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave.

Gee, J.P. (2007). Good video games + good learning: Collected essays on video games, learning and literacy. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

Huizinga, J. (1950). Homo Ludens: A study of the play element in culture. Boston: Beacon.

Jenkins, H. (2007, January 3). Reality bytes: Eight myths about video games debunked. The Video Game Revolution. Retrieved March 1 from: http://www.pbs.org/kcts/videogamerevolution/impact/myths.html

Johnson, S. (2006). Everything bad is good for you: How today's popular culture is actually making us smarter. London: Riverhead Books.

Lingual Gamers. (2007). Language learning with new media and video games (unpublished thesis). Retrieved February 28, 2008 from: http://lingualgamers.com/thesis/

Mawer, K. (2008). Language learners, teachers & computer games. Retrieved March 1, 2008 from: http://kylemawer.wikispaces.com

Poole, S. (2000). trigger happy--the inner life of videogames. New York: Fourth Estate.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon 9, 5. Retrieved February 1, 2008 from: http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf#search=%22prensky%22digital%20native%22%22

Prensky, M. (2004). Digital game-based learning. New York: McGraw Hill.

Prensky, M. (2006). Don't bother me, Mom—I'm learning! Minnesota: Paragon House Publishers.

Sim Teach (n.d.). http://www.simteach.com/wiki/

Stevens, V. (2006). Second Life in education and language learning. TESL-EJ, 10(3). Retrieved January 13, 2008 from: http://tesl-ej.org/ej39/int.html

Vickers, H. (2007). Second Life education gets real: New methods in language teaching combine virtual worlds with real life. Retrieved February 15, 2008 from: http://www.avatarlanguages.com/pressreleases/pr3_en.php.

Escape From the Bar: http://www.gotmail.jp/apps/bar_e.html

Grow Cube: http://www.eyezmaze.com/grow/cube/

MOTAS (Mystery of Time and Space): http://www.albartus.com/motas/

Nesquik: http://www.nesquik.com/games/nesquikQuest.aspx

Quest for the Rest: http://www.questfortherest.com

Samorost 2: http://www.samorost.net/samorost2/

World of Warcraft: http://www.worldofwarcraft.com

|

© Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor's Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |