September 2006

Volume 10, Number 2

| Contents | | | TESL-EJ Top |

|

September 2006

|

||

|

| Title: | Active Listening in English |  |

| Level: | Pre-Intermediate | |

| Publisher: |

Sky Software House 7 Woodland View, Fairfield Rd, Buxton SK 17 7DJ, United Kingdom http://www.skysoftwarehouse.com mail@skysofwarehouse.com | |

| Product Type: | CD-ROM for individual machines and networks | |

| Platform: | Windows | |

| Minimum System Requirements: |

Pentium I, Windows 98+, 64 MB (RAM) and approximately 170MBs of hard disk space. Recommended: 1027X768 screen resolution and True or High Colors | |

| Price |

Educational price: 1 user: £70 2-5 users: £ 95 6-10 users: £ 130 20 users: £170 40 users: £240 Individual price: £25.00 which also includes other products by Sky Software House (The Phonemic Alphabet in English, Similar Sounds, Word and Phrasal Stress, Stress and Rhythm, and Rhythms from Rainland). | |

| ISBN | 0 9587330 7 4 | |

According to the Sky Software House website, Active Listening in English is language learning software that provides extensive listening practice for adults and young learners of English at the pre-intermediate level. It is most suitable for self-guided study or for additional listening practice as a part of class/lab time.

Active Listening in English comes on one CD-ROM and is easy to install. Installation is quite straightforward and no technical difficulties were encountered while testing the program. The interface is user-friendly with helpful pop-up labels for each icon/button, and clearly organized units. The units are easy to navigate, but it is not possible to move directly from one exercise to the next without going back to the Main Menu. Within the program, there is no Help icon, but the CD-ROM contains a Help file that addresses common troubleshooting problems. The cover of the CD-ROM gives system requirements and installation instructions. The program, which can run on a network or individual computer, does not require an internet connection.

The program consists of five units, each of which contains four types of exercises: Listening for Information, Listening and Responding, Listening and Note-taking, and General Listening. The first three exercise types have three distinct exercises each; General Listening has one. Figure 1 shows the main menu and exercises in Unit 2.

Figure 1. Main Menu and exercises in Unit 2

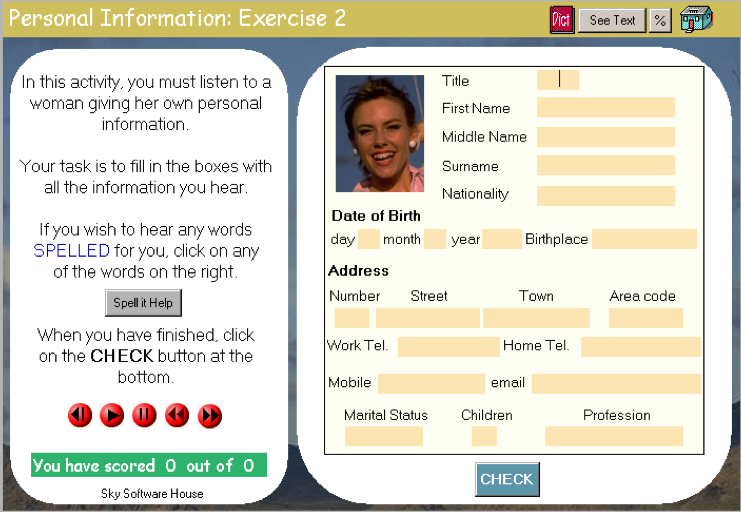

Several types of listening texts are used in this program, including monologues, dialogues, and dialogues in which the learner takes part. There are also longer talks and interviews. The learner responds to listening input by clicking on the graphic or text, dragging and dropping boxes, or typing in information. The instructions, which are displayed on the left-hand side of the screen, are clear and easy to follow. In most of the exercises, learners can control the audio using a controller that allows them to pause, fast forward, and rewind the audio. Figure 2 shows a sample screen from one of the exercises with these buttons in red. In some exercises, there is only a play button and learners can replay the segment, but not rewind, fast forward, or pause.

Figure 2. Sample screen from an exercise

There are several features found in all of the exercises. All of the exercises have a transcript that can be accessed by clicking the "See Text" icon. However, the transcript is available only after all the answers have been entered and checked. Transcripts are often used as a form of help in computer-delivered listening comprehension exercises, and CALL research has shown their effectiveness (Hsu, 1994; Liou, 1997). There is also a dictionary icon that opens a glossary of words used in the exercise. The third button has the % symbol on it and opens a pop-up window displaying the percentage of correct answers completed in the session. Learners can monitor their scores by looking at the green box at the bottom of the left part of the screen which displays the total number of points and the points they scored in the exercise. The program also contains a Teacher Mode (see bottom of Figure 1) which allows teachers to print out transcripts of all exercises.

Active Listening in English exposes learners to unsimplified language at a normal native-speaker's speech rate. Although there are speakers of American English in some of the texts, the variety of English spoken is predominantly British. The program covers a variety of topics of general interest, such as football, small talk at a gathering, Red Bull energy drink, and William Shakespeare's life, and presents them in an interesting way. The content is engaging and allows for extensive listening practice. The tasks used in the program are authentic because students might actually encounter many of them (checking-in at the airport, ordering food, booking cinema tickets by phone) outside the language classroom. However, the content might be more appropriate for adults than for young learners because some aspects of the content are not appropriate for younger students. Examples of such content include references to religious discrimination, people smuggling, making advances in a bar, and drinking alcohol at parties.

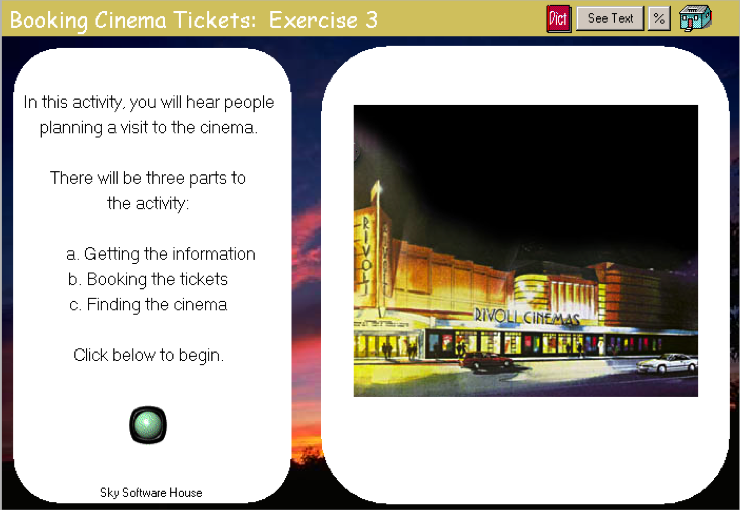

The units in Active Listening in English increase in difficulty in terms of task complexity. For example, the Listening and Responding exercises in Unit 5 have three parts which build upon one another so that learners go through three listening activities to complete the task of buying tickets for the cinema (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Three parts of a listening task

However, the overall language difficulty level remains the same throughout the program. The language occasionally contains very complex vocabulary and is delivered at a normal native-speaker speech rate. This may seem very fast to pre-intermediate learners. These features together can make language processing difficult for learners. For example, the speaker in Unit 2 uses words such as mammals, vegetation, distinctive, and extinction to describe animals and places where they live. The publisher has made the task easier for students by providing very good photos of animals that contain clues as to exactly which animal the speaker is describing. In addition, the aforementioned glossary contains some of the unknown words, but that does not always help with understanding the meaning of certain abstract words. While it can be rightly argued that in a listening-for-information type of activity, the learners do not need to understand every single word to get the gist and that they should be exposed to authentic language, the task could be made less challenging by allowing learners to control the audio (pause, rewind, and fast-forward) and/or allowing learners to access the transcript while listening.

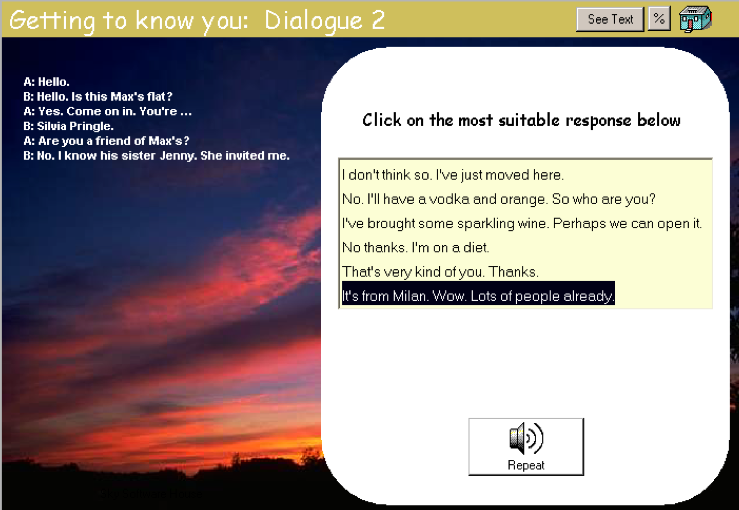

The most interactive exercises in the program are the Listening and Responding exercises where learners take part in a dialogue. The learner first listens to the speaker and then responds by selecting a line from the list. Once the learner clicks on the right response, the response is spoken and appears on the screen. In this way, the transcript of the dialogue is gradually revealed. For example, in the second dialogue in Unit 2 (Getting to know you), the learner takes on the role of Silvia who has arrived at a party and introduced herself to the hostess. Figure 4 shows the learner building up the dialogue.

Figure 4. Learners take part in the dialogue by selecting appropriate responses

In Unit 3, the task becomes more difficult in that the learner takes part in a conversation between three speakers by playing two of the three roles.

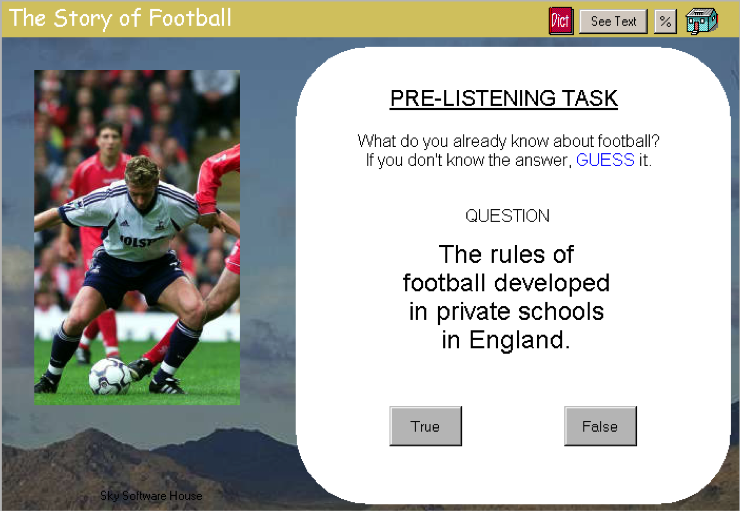

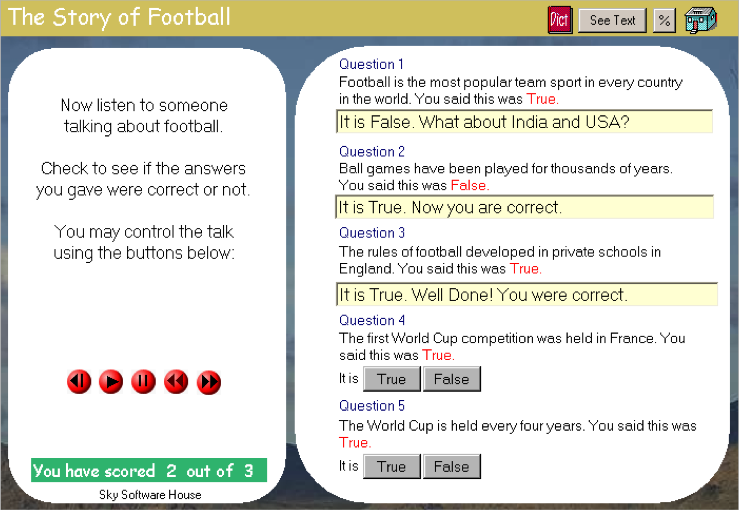

Some of the General Listening exercises have a pre-listening component (e.g., Football, William Shakespeare). For example, in the Football unit, learners answer a set of true/false questions about the content of the talk/interview to which they are about to listen (see Figure 5). Then, they listen to check and revise their answers. These types of pre-listening tasks, which are often overlooked in CALL software (Hubbard, 1996), can be additionally motivating for students because they better prepare the learners for the listening.

Figure 5. A pre-listening exercise

Figure 6. Learners listen and check their predictions

As can be seen in Figure 6, the program provides item-specific feedback and either praises the learner for knowing the answer or hints at the correct answers if the learner did not guess correctly. The excellent way in which this exercise is set up allows for learner schema activation and the use of previous knowledge about the topic. This makes the task more interesting and the listening practice more focused.

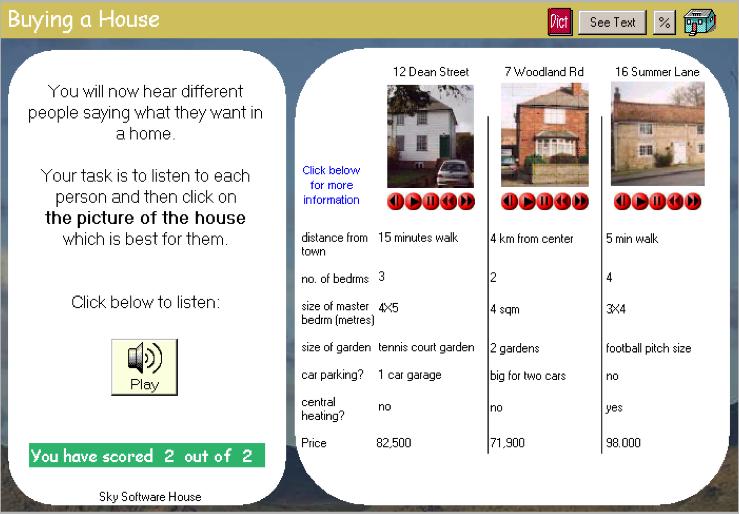

Listening and Note-taking exercises are fill-in-the-blank exercises where the learners listen to the aural input and type in the missing words or phrases. For instance, they fill out a form, complete a class timetable, or take a telephone message. The three exercises in Unit 4 make the best use of learners' notes on houses for sale because in the follow-up part, learners use their notes to choose the most suitable house for different speakers (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Learners use their notes to complete the task

Thus, we can see how a common type of exercise in the program (there are 12 note-taking exercises) has been slightly modified to create welcome variety and increase student motivation. One possible way to modify the exercise further would be to ask the students to take down notes without specifying any categories beforehand. This would raise student awareness of the importance of good note-taking skills, an important aspect of listening in academic settings.

In Active Listening in English learners have two options for getting help with processing the aural input: the transcripts and the dictionary. As mentioned before, the transcripts cannot be opened while the learner is doing the exercise. Also, once learners see the transcript, they cannot go back and try to correct the answers themselves. This design discourages the use of transcripts. However, it would seem that when exposing learners at the pre-intermediate level to authentic aural texts, they need to be given tools that help processing, beyond simply replaying the segment a number of times. Instead of supplying the correct answers, a better design option would be to allow learners to see the transcript after a certain number of unsuccessful attempts. This way the learner would go between reading the transcript and listening to the aural text and take better advantage of the material by receiving it in two different modes: visual and verbal (Jones, 2006). If there is a concern that learners would misuse the transcript and rely solely on reading when doing the exercises, the teacher could be allowed to choose (in the Teacher Mode) whether or not students can display the transcript depending on whether the students are practicing or being tested.

Access to the dictionary is a helpful feature of the program but it usually does not include all of the words from the exercise, some of which may be unknown to the learners at that level. Therefore, it would be more accurate to call it a short glossary. A more comprehensive glossary would be highly useful, as would a link that takes learners to an on-line dictionary (providing they have an internet connection). Another option would be to gloss difficult words in the transcript.

The program provides only positive feedback in textual form ("Correct"), while clicking on the incorrect answer lowers the score one point. A lack of informative negative feedback encourages a trial-and-error approach to answering questions. The learners would profit from getting to know why the answer they selected was incorrect and while this design requires more production time it is pedagogically worthwhile. In exercises where answers are typed in, the program does not tolerate the lack of proper capitalization and punctuation or minor spelling errors; this may be frustrating for learners. The publishers probably had this issue in mind when they decided to provide the "Spell it Help" button in some Unit 1 exercises (see Figure 2). It would be nice to have this option in other exercises as well so that learners could click on any word and get help spelling it. Additionally, more flexibility with answer processing (e.g., accepting minor spelling errors) should definitely be allowed.

Feedback on one's performance is given as an overall percentage (for example "You have scored an average of 67% during this session") which is not very meaningful. It would be more useful to have the scores displayed as points by units or exercises in addition to cumulative percentage scores. This would help the learners keep track of their progress as well as give the teacher a better idea of what exactly students did and how well.

While many useful features are implemented in Active Listening in English, future versions of the program could benefit from incorporating one or more of the following suggestions:

Active Listening in English helps learners develop their listening skills through interaction with engaging materials using a variety of listening tasks. The program is best suited for adults learning English at home or in class during lab time. However, both of these groups and their tutors/teachers would benefit considerably from a student workbook and teacher manual. The program seems best for motivated pre-intermediate learners who would like exposure to everyday spoken British English but who get discouraged by language that is too difficult for their level. A design that encourages better use of help options, includes pre-listening and post-listening exercises, and allows for more specific feedback could make Active Listening in English an even better product in future versions.

Hsu, J. (1994). Computer assisted language learning (CALL): the effect of ESL students' use of interactional modifications on listening comprehension. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.

Hubbard, P. (1996). Elements of CALL methodology: development, evaluation, and implementation. In M.C. Pennington (Ed.), The power of CALL. Houston, TX: Athelsan.

Jones, J. (2006). Listening comprehension in multimedia environments. In L. Ducate & N. Arnold (Eds.), Calling on CALL: From theory and research to new directions in foreign language teaching. (pp. 99-125). CALICO Monograph Series, 5. San Marcos, TX: CALICO.

Liou, H.C. (1997). Research on on-line help as learner strategies for multimedia CALL evaluation. CALICO Journal, 14 (2-4), 81-96.

Rost, M. (2002). Teaching and researching listening. London, UK: Pearson Education.

Maja Grgurovic is a doctoral student in the Applied Linguistics and Technology Program at Iowa State University. She holds an MA degree in TESL/Applied Linguistics from Iowa State. Her research interests are listening and multimedia CALL, software design, and integration of technology into language teaching and teacher education.

|

© Copyright rests with authors. Please cite TESL-EJ appropriately.

Editor's Note: The HTML version contains no page numbers. Please use the PDF version of this article for citations. |